It was a big year at Cornell Tech.

Our students, faculty and staff built innovative technologies and products. Construction of our Roosevelt Island campus made significant progress in preparation for classes next fall . And initiatives like K-12 education and Women in Technology and Entrepreneurship in New York (WiTNY) continued to make a big impact in the community.

Take a look back at 2016 with some of our favorite stories and get excited for more great things to come in 2017.

How Shortened URLs Can Be Used to Spy on People

Research done by Professor Vitaly Shmatikov revealed how shortened URLs can be easily hacked and can put sometimes-sensitive information at risk.

Ron Brachman Joins the Jacobs Technion-Cornell Institute at Cornell Tech as the New Director

The Jacobs Technion-Cornell Institute announced Ron Brachman as the new director of the institute. Brachman, an internationally recognized authority on artificial intelligence, comes to the Jacobs Institute from Yahoo where he was the Chief Scientist and Head of Yahoo Labs.

2016 Cornell Tech Startup Award Winners Announced

In the second Cornell Tech Startup Awards, four startups developed in Startup Studio received $80,000 in pre-seed funding and $20,000 worth of co-working space.

OneBook to Rule Them All: A Cornell Tech Startup Brings Mixed Reality to Reading

OneBook was built by two Connective Media students at the Jacobs Technion-Cornell Institute using mixed reality to bring digital content to physical surfaces.

Making Global Connections in Healthcare with Connective Media

Two Connective Media students conducted research with Assistant Professor Nicola Dell in Lesotho, Africa to develop a digital system for tracking biological samples used in diagnostic services in rural areas of the country.

Runway Startup Postdoc Assaf Glazer Has Reinvented the Baby Monitor

Nanit is a baby monitor like no other. Using computer vision and machine learning, Nanit provides parents with easy-to-understand insights into their child’s sleep patterns. This year, Nanit raised $6.6 million in funding.

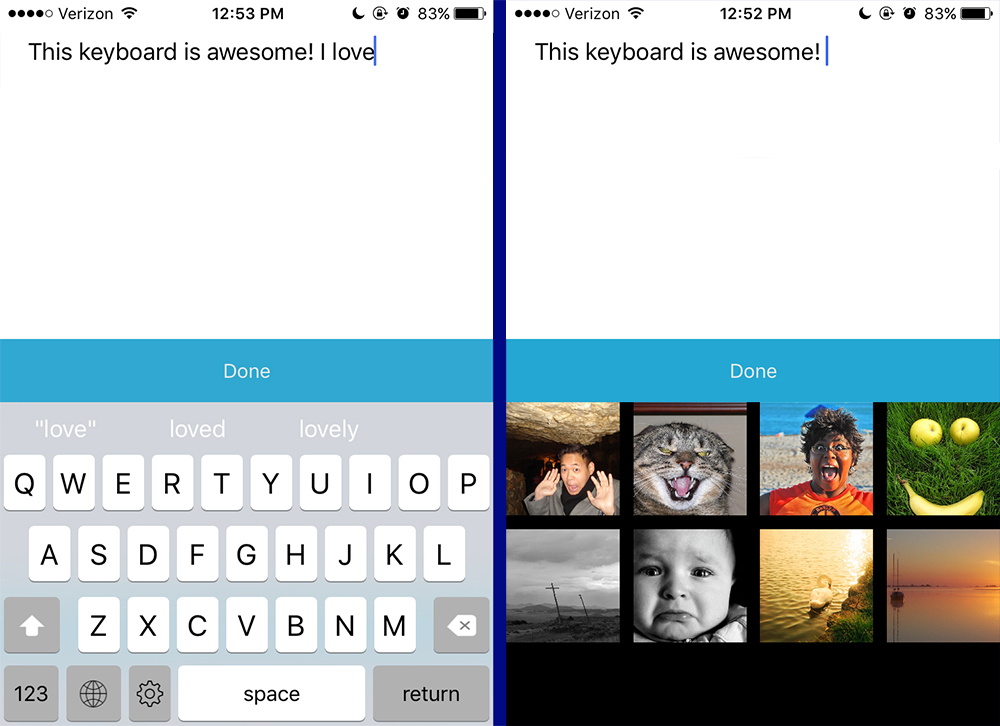

This Retainer Doesn’t Change Teeth — It Changes Lives

A team of Connective Media students at the Jacobs Technion-Cornell Institute developed a retainer-like device that allows the mobility impaired to manipulate connected devices using their tongue.

The New York Times: The Innovation Campus — Building Better Ideas

In an article in the New York Times, Cornell Tech’s future home on Roosevelt Island was featured for leading the charge on innovation in college campuses.

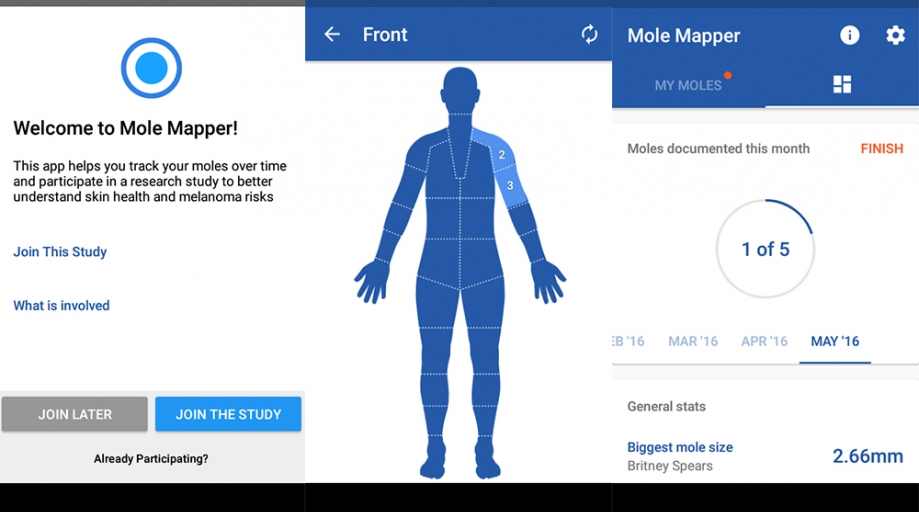

First ResearchStack App, MoleMapper, Launches on Android

ResearchStack — the open source framework developed by Associate Dean and Professor Deborah Estrin — launched it’s first app, MoleMapper, bringing mobile medical research to Android devices.

Where Computer Science and Community Health Meet

Sonia Sen, Technion-Cornell Dual Masters Degrees in Health Tech ’17, is working to streamline healthcare in Harlem.

Cornell Tech Alum Builds ‘Dreamteam’ to Create All-Star Tech Teams

What started as a Startup Studio project ended up being a valuable tool for Cornell Tech to build balanced and passionate teams.

Hillary for America CTO Stephanie Hannon Discusses Her Life in Tech

Earlier this year, Cornell Tech, in partnership with CUNY, launched the Women in Technology and Entrepreneurship in New York (WiTNY) initiative to empower young women to pursue careers in technology. They hit the ground running, developing programs, awarding scholarships (41 total), and even bringing in Stephanie Hannon, accomplished engineer and the first female CTO of a major party’s presidential campaign.

Media Highlights

Tech Policy Press

Content Moderation, Encryption, and the LawRELATED STORIES

Winternship Recap 2018