AJ Capital Partners and Cornell University Announce New Graduate Hotel On Roosevelt Island Campus

Categories

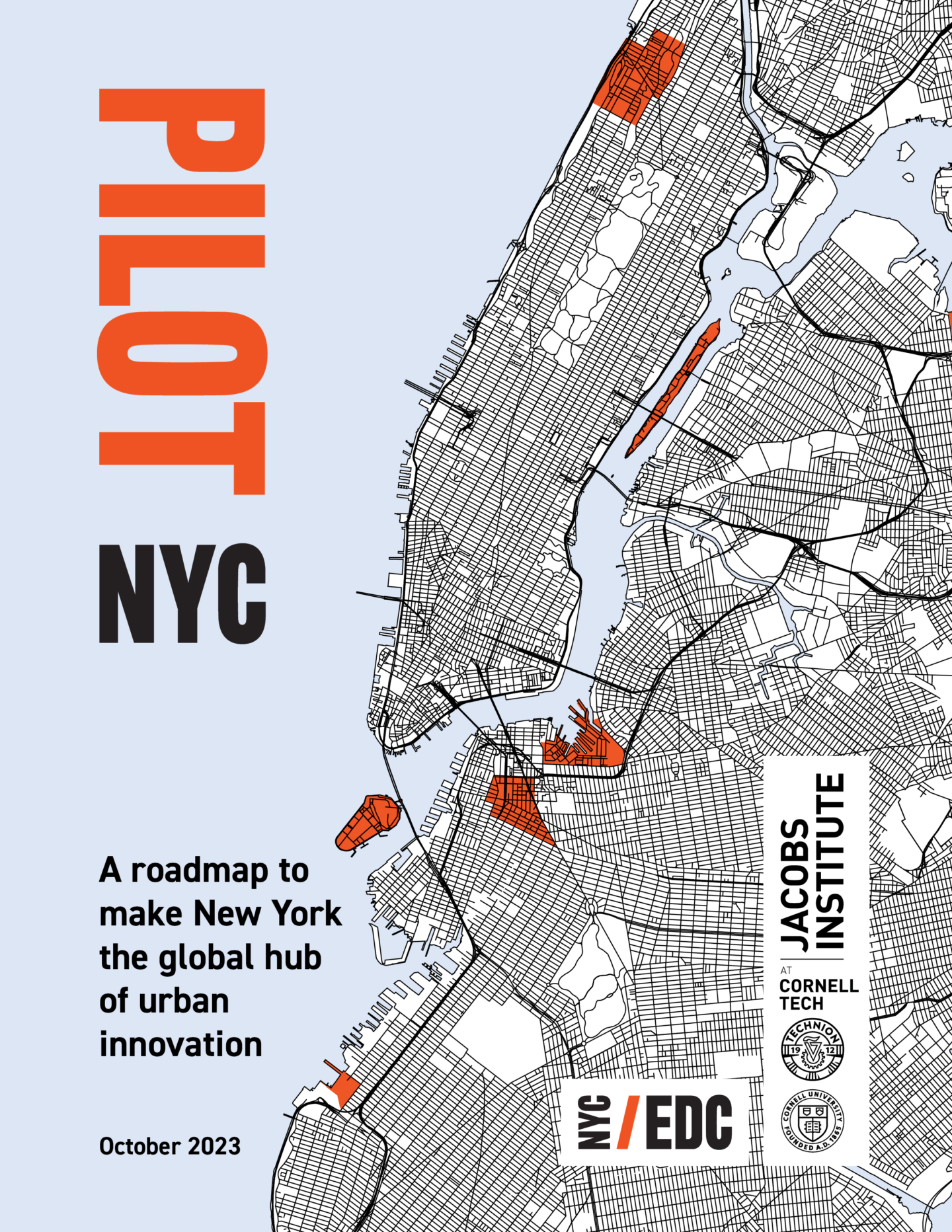

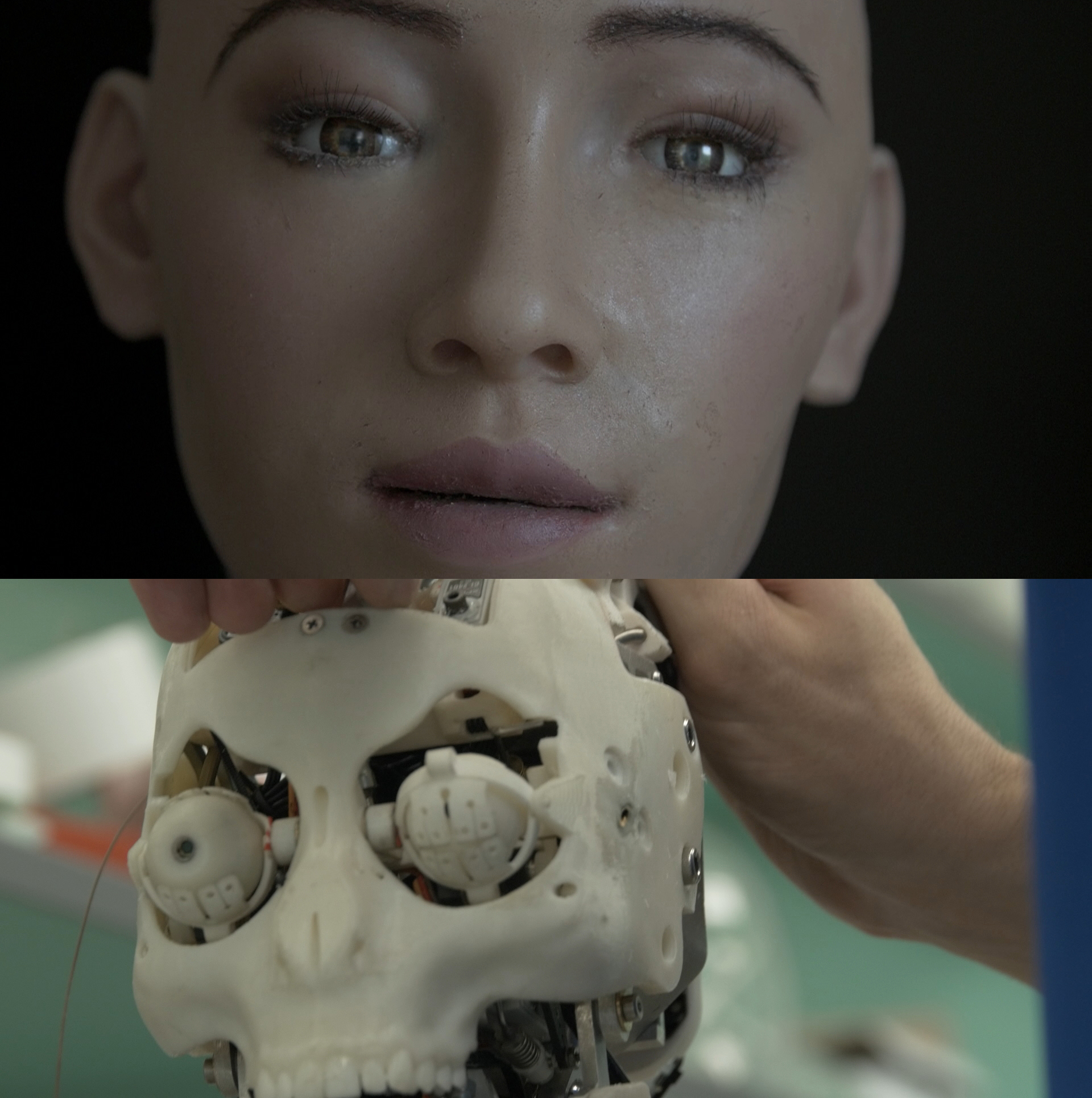

AJ Capital Partners and Cornell University announced plans to build a hotel on the university’s new Cornell Tech campus on Roosevelt Island. Cornell Tech, which will open the first phase of the new campus September 2017, is a revolutionary model for graduate education, extending Cornell University’s research and academic prowess to the heart of New York City by bringing together faculty, business leaders, tech entrepreneurs and students in a catalytic environment to produce visionary results.

AJ Capital Partners will open “Graduate Roosevelt Island,” a 196-room ground-up hotel development with panoramic views of the Manhattan skyline in 2019. Designed by world-class architectural firm Snohetta, the hotel will be located in the heart of the campus alongside the Verizon Executive Education Center, which will have conference, executive program and academic workshop space, also opening in 2019.

“Graduate Roosevelt Island is the type of transformative project that has come to epitomize our company,” said Ben Weprin, founder and CEO of AJ Capital Partners. “The hotel will sit prominently at the gateway to Cornell Tech, the most innovative academic campus in the world; and will offer guests, campus visitors and Roosevelt Island citizens a truly distinctive and unique experience. We couldn’t be more excited to partner with Cornell University and to introduce Graduate Hotels to New York City.”

“Cornell is thrilled to partner with AJ Capital Partners for a hotel on our Roosevelt Island campus. Their unique aesthetic combined with the world-class architecture of Snohetta will be an asset for Cornell, the Roosevelt Island community and New York City,” said Dan Huttenlocher, Cornell Vice Provost and Dean of Cornell Tech. “The Graduate Roosevelt Island hotel will reflect the unique history of the island and, along with the Verizon Executive Education Center, it will create a place where the entire tech community can convene in New York City, expanding the impact our campus will have on technology beyond its degree programs.”

Created for travelers who seek memory-making journeys, Graduate Hotels are part of a well-curated, thoughtfully crafted collection of hotels that reside in the most dynamic, university-anchored markets across the country. Every property celebrates and commemorates the optimistic energy of its community, while offering an extended retreat to places that often played host to the best days of our lives. Locations include Ann Arbor, Mi.; Athens, Ga.; Charlottesville, Va.; Madison, Wi.; Oxford, Ms.; and Tempe, Az., as well as Berkeley, Ca.; Lincoln, Ne.; Minneapolis, Mn; and Richmond, Va. slated to open in 2017, and Bloomington, In. and Seattle, Wa. in 2018.

The hotel’s iconic slender profile marks the entrance to the campus while offering guests unobstructed views of the skyline through floor to ceiling windows. The hotel’s comfortable residential aesthetic will reference the history of Roosevelt Island, while also capturing the spirit of innovation inspired by the Cornell Tech campus. The property will include a full-service restaurant, rooftop bar with expansive views of Manhattan, and 5,200 square feet of flexible meeting and event facilities for hotel guests and the Roosevelt Island community.

Opening September 2017, the first phase of Cornell Tech’s Roosevelt Island campus will include three buildings: The Bloomberg Center, the campus’ first academic building; The Bridge, a building for innovative companies to locate on campus; and The House, a residential building for students, faculty and staff that aims to become the world’s first high-rise residential building constructed to “Passive House” energy efficiency standards.

When fully completed, the campus will span 12 acres on Roosevelt Island and house approximately 2,000 students and hundreds of faculty and staff. The campus master plan was designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill with James Corner Field Operations, and includes a number of innovative features and facilities across a river-to-river campus with expansive views, a series of green, public spaces, and a seamless integration of indoor and outdoor areas. The campus will be one of the most environmentally friendly and energy-efficient campuses in the world.

For more information on Graduate Hotels, please visit www.graduatehotels.com.

About AJ Capital Partners

Adventurous Journeys Capital Partners, based in Chicago, is an accomplished team of hospitality and real estate investors whose innate passion is to create a one-of-a kind portfolio of timeless assets. The counter-culture investors acquire, design and develop transformative real estate throughout the United States, Mexico, and the Caribbean. In fall 2014, AJ Capital Partners launched the Graduate Hotels collection. AJ Capital Partners continues to grow its portfolio of lodging investments, firmly establishing the group as visionary leaders in the lifestyle-driven investment industry. For more information on AJ Capital Partners, please visit www.ajcpt.com.

About Cornell University

Located in Ithaca, N.Y. and New York City, Cornell is a private, Ivy League university and the land-grant university for New York State. Cornell’s mission is to discover, preserve, and disseminate knowledge; produce creative work; and promote a culture of broad inquiry throughout and beyond the Cornell community. Cornell also aims, through public service, to enhance the lives and livelihoods of our students, the people of New York, and others around the world.

About Cornell Tech

Cornell Tech brings together faculty, business leaders, tech entrepreneurs, and students in a catalytic environment to reinvent the way we live in the digital age. Cornell Tech’s temporary campus has been up and running at Google’s Chelsea building since 2013, with a growing world-class faculty, and more than 200 masters and Ph.D. students who collaborate extensively with tech-oriented companies and organizations and pursue their own start-ups. Construction is underway on Cornell Tech’s campus on Roosevelt Island, with a first phase due to open September 2017. When fully completed, the campus will include 2 million square feet of state-of-the-art buildings, over 2 acres of open space, and will be home to more than 2,000 graduate students and hundreds of faculty and staff.